This is the amazing photograph ...Taken in New York City. It was taken in City Hall in April 1865. It is the only photo of Lincoln in death. It was supposed to have been destroyed by Stanton, Lincoln's Secretary of War...But in 1952, the impossible seemed to happen to a 14 year old boy!

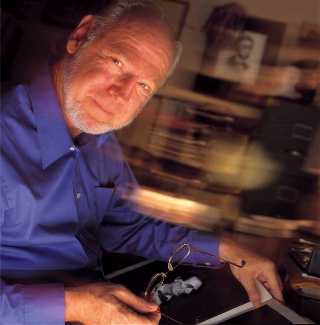

Dr. Ron Rietveld

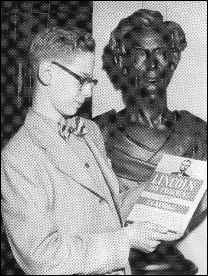

Dr. Ron Rietveld A very lucky young man

A very lucky young man When I was a boy, from the age of I would say maybe 6 years of age. I started to devour everything I could on Lincoln. By the age of 10, I had an encylopedic brain trust of everything dealing with Lincoln.

I was allowed in local libraries and read the adult books as there was little left for me to read in the childrens sections...I read, and read and studied. Soon it encompassed much of history itself...No subject was to be neglected...I as a young boy had a heart murmur and I was told I could not play sports or run around so that energy was placed in study. In my local library were a collection of very old books and papers and I used to pour through these books to learn more of the more odd areas of history and the forgotten topics that once were so important. That was a treat. I still do that.

Today as a more mature man I have this amazing resource in my mind. I am blessed to have at my call this tremendous amount of information on history. I am very blessed in this fact.

When I read the story of the young man who discovered the last picture of Abraham Lincoln in death, I was taken so by his story. Reading the libraries dry on history, having a heart murmur, and not being allowed to run around, and talking to all the old timers he could, I found a kindred spirit. I have found a first person account with this amazing man Ron Rietevld on "Abraham Lincoln online". It is a wonderful resource.

I think his story is most amazing and very much worth sharing. I have added two oral histories with him. They are long but well worth reading. He was and is a most fortunate man. I understand the special importance with touching our past..I was lucky in the area dealing with Thomas Edison and knowing many who knew him...So here is his story, a most amazing find......The dream of every youthful historian.

The Magnificent Find

Discovering the Lincoln Death Photograph

More than 50 years ago a 14-year-old boy found a photograph of President Abraham Lincoln in his coffin taken on April 24, 1865, in New York City. The discovery startled historians, because Edwin M. Stanton, Lincoln's Secretary of War, had ordered this photograph to be destroyed. Stranger yet, the one surviving print remained with Stanton, whose son preserved it. This is a first-person account of the discovery, as told by Dr. Ronald Rietveld, professor of history, California State University-Fullerton.

As a boy I got interested in Lincoln about 1942. I had a heart murmur and wasn't allowed to play sports. At the time, it was thought that children who had heart murmurs might just fall over dead. So I had to do something, and I turned to the world of reading. Early on, American history attracted me and Washington and Lincoln became my heroes. Then I began to write people. I wrote to the last living Civil War veterans as a boy -- there were still seven alive in 1950 when I wrote them. Supposedly the last one died in 1959 at 117; there's a debate about that particular one.

I also wrote to Carl Sandburg, the poet who was known for his Lincoln biographies. When I was in fifth grade the Des Moines Public Library let me check out books in the adult section because I had devoured everything on Lincoln and the Civil War and George Washington in the children's section.

The story begins back in the 1950s. I had read an article about Judge James W. Bollinger, who was a Lincoln collector in Davenport, Iowa. It was a nice feature article in a Des Moines, Iowa, newspaper about how he was collecting books and signatures and documents of President Lincoln. And so I wrote Judge Bollinger, which meant that Iowa's oldest Lincoln enthusiast, and probably Iowa's youngest, were correspondents.

Later I read that Judge Bollinger died and had given his collection to the University of Iowa at Iowa City. So in 1951 I wrote a letter to the university and said I had known the judge as a correspondent and as a friend and was wondering if I could attend the dedication of the Bollinger Lincoln Collection at the university in November. I was 14 years old at the time. I hadn't heard anything at all and I thought they didn't get the letter or certainly had ignored it because I was a boy.

Then I got a phone call from Clyde Walton who was in charge of the collection and later became State Historian of Illinois. Clyde said in essence: "Are you for real? Were you really a friend of Judge Bollinger, did you really correspond with him?" When I said I had, he replied, "You need to come and be our guest at the dedication of the collection on November 19 and 20." I told him I would love to. My parents agreed, dressed me up in my finest clothes, and put me on aboard the Rock Island Rocket in Des Moines.

I went by myself to Iowa City and was met there by a relative of the family lawyer and they took me home as their guest. When I arrived at the university for the dedication all the great Lincoln scholars were there except Carl Sandburg: Harry Pratt, State Historian of Illinois; Paul Angle, Director of the Chicago Historical Society; Fern Nance Pond, the New Salem historian; Louis Warren of the Lincoln National Life Insurance Company Foundation and Museum; Harry Lytle, a friend of Judge Bollinger's from Davenport; and Benjamin Thomas, who was then finishing his Lincoln biography. Approximately 60 collectors and students were present at the evening banquet which opened the dedication. Paul Angle was the guest speaker at the event. I met them all and we became good friends.

There were two days of dedication, including some speeches, and I still have a copy of the official results. While there we made a film (which still exists) of the scholars at the dedication and I was included in that group. Harry Pratt took a liking to me and asked, "Ronald, have you ever been to Lincoln's home or tomb?" When I said that I hadn't, he replied, "How would you like come as our guest and stay with Marion and me?"

Marion was his new wife and one of the assistant editors of The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. When I agreed to come, he said, "I tell you what, we'll let you know when everything is set and I'll mail you a postcard. You just get on a bus and come to Springfield and Marion and I will meet you."

The Momentous Trip to Springfield

So Mother put me on the bus at Des Moines; I changed busses alone at Galesburg, Illinois -- I don't think I'd ever let my kids do what I did. When I got to Springfield the Pratts met me. From there they took me to New Salem to a pageant that evening and I stayed in their home. On Sunday morning, July 20, 1952, we were supposed to get up and head for church but we overslept.

Instead, they decided after breakfast that Harry would take Marion to the Lincoln Home. The second floor was where Virginia Stuart Brown lived. (The second floor of the home was not open then to the public.) Virginia was a cousin of Mrs. Lincoln, a great-granddaughter of John Todd Stuart. So Marion stayed with her and continued to work on the galley proofs of the Collected Works, which I have today in my own collection.

Harry and I went off to the Centennial Building on the state complex grounds. He was writing a review of a book and took me to the Lincoln-Horner Room and said he would open up the file of the Nicolay-Hay Collection. When he took me to the file in the library, he said I should feel free to take anything out, walk into the Lincoln-Horner Room, sit down and look at it, but I must return everything exactly the way I found it. He was going to write his review meanwhile. So he went off to his office and I went to the file.

The Eye-Popping Discovery

I started going through the Nicolay-Hay papers. These were the papers John Hay's daughter gave to the Illinois State Historical Library in 1943 as a result of the writing of the 10-volume set of the life of Lincoln. [John Nicolay and John Hay were White House secretaries during the Lincoln administration.] I came to a file called X:14. I'll never forget the number -- it's burned in my memory. Of course, the burning came later. I took it in, opened it up, and was reading Nicolay's notes about Mrs. Lincoln's visit to City Point [Virginia] and the fiasco that occurred there after her head had been hit on the top of a carriage during a very bumpy ride.

When I finished, I saw an envelope laying there from 1887, sent from Minnesota to John Nicolay at Georgetown. I opened it and there were two pieces of regular stationery paper plus another piece of regular stationery folded in thirds; I laid the last piece aside. I read the first piece, which was the letter from Lewis H. Stanton to John Nicolay, saying in essence, "I have found this in my father's papers and perhaps you'd like to use it," and then he said, "What did you think of McClellan's story?" I forgot about the contents. I folded it, put it back in the envelope, put it back in the manilla folder, and realized I left something out.

I opened up the folded sheet of plain stationery and there lay a faded brown photograph. I thought it was sepia tone at first, and then I saw what it was immediately. I knew Lincoln photography fairly well at 14 and knew that this picture, if it was indeed a photograph, did not exist. I had a copy of the May 6, 1865, issue of Harper's Weekly at the time, in which the scene is sketched, because there were no photographs published.

So I knew where it was taken -- it was New York City, and when it was taken -- April 24, 1865, and I picked it up and ran in and said, "Harry, look at what I just found! This is a picture of Lincoln in his coffin taken in New York City at the time of the funeral!"

He looked at it and said, "Oh! Let's check you out to see if you are right." So we walked all the way from his office to the Lincoln-Horner Room and he got out two different volumes and opened them and said, "You've got the right date, you've got the right place. Now can you keep still?" When I asked why, he said, "Well, we'll have to do research on this before we release it to the country."

I said, "Yes, Harry, I won't say anything." You have to realize, I'm 14 and have a lot of chutzpa for a boy of that age so I said, "I won't say a word provided you give me a copy of the photograph." He promised to do that. To spin ahead, Harry kept his word. I still have the copy he gave to me. Meanwhile, of course, I kept still.

The Photograph Makes National News

About 5:30 the morning of September 14, 1952, my mother was shaking me awake, saying that Grandpa Rietveld had just called and said my picture was on the front page of the Des Moines Register and wanted to know if Mother knew about this thing. Mother said, "What is this?" Her famous line was, "What did you do wrong? What happened?" And I said, "It was that Lincoln picture I found this summer in Springfield."

She demanded, "What Lincoln picture?" I answered, "The one I found when I was with Dr. Pratt." Then, of course, I told the story. The phone began to ring. The Des Moines Register wanted to do a feature article on it and ultimately they came out. Harry had given my name in the main story to the Associated Press, so my name and the photograph appeared across the country. Harry collected several of the articles and sent the clippings to me as a gift.

Then Life magazine picked up the story from Stefan Lorant because Marion wanted to give the picture to him for his volume on Lincoln photographs. So he wrote the September 15, 1952 article that's in Life. My name did not appear in the article and Louis Warren noticed it, saying that should be corrected. He said I should write a letter to Life, so I did and they checked with Dr. Pratt to see if it was true. In the October 6, 1952 issue, Dr. Pratt talks about me as a Lincoln scholar and validated that I found the photo. So in the Letters to the Editor you will find the picture and his comments. After that, when it was released in Lorant's book, Louis Warren told him he should send me a complimentary copy of his new book. Lorant did so, saying it was "for your magnificent find."

There's a little addendum to this story. I later received a book in the mail from Dr. Pratt -- one of [James Fenimore] Cooper's novels. It belonged to a set owned by the Chenery House in Springfield (the hotel where the Lincolns stayed just before leaving town). Lincoln took another volume from the set with him to Washington. Dr. Pratt had the whole collection, but he broke it up and sent me one book in appreciation for finding the Lincoln photo.

Meeting the Last Person to See Lincoln in Death

Dr. Rietveld also had the privilege of becoming acquainted with Fleetwood Lindley of Springfield, Illinois, the last surviving person to see Lincoln in his coffin. Lincoln's remains had been moved many times since arriving in Oak Ridge Cemetery, and a small number of people saw the coffin opened one last time to ensure it actually contained Lincoln's body. Here is Dr. Rietveld's account:

This story begins with our friends George and Dorothy Cashman, curators of the Lincoln Tomb in Springfield. George came there in 1950; I first met him in 1952 and he was there for about 20 years. My wife Ruth and I often stayed with the Cashmans in their home when I was a graduate student at the University of Illinois. One day they said they would show us the old Clayville Tavern west of Springfield, which had been opened to visitors. They had a mutual friend they thought we would enjoy meeting.

So they drove us out to Clayville Tavern, and there was Fleetwood Lindley. This would have been the fall of 1962 because he died in 1963. I asked him, because I was told he was present, to tell the story of his seeing Lincoln's body. He began by telling me that in 1901 his father, who was a member of the Lincoln Honor Guard, was going to be present for the moving of the body from outside where it was, to inside the Lincoln Tomb.

He said paper was put over the windows so no one could see into the tomb. His father told him that he would call the principal of his school and tell him to contact Fleetwood in class if he could come out to the tomb. So he said, "If you get a request from your principal, you get on your bicycle and immediately go out to the tomb. Tell no one."

So the principal told Fleetwood that his father had called and sent for him to go to the tomb. He got on his bike and rode there and parked his bicycle. His father met him and they took him into the chamber where he saw several of the Honor Guard plus the two plumbers who had opened the coffin in 1884. These two men had sealed it in 1884 and now they were going to re-open it.

He said he watched them as they opened the lead lining of the coffin. Inside the coffin was the lead lining, so the president's remains were sealed in lead. The plumbers with their torches opened the lining very carefully and rolled it back. When that happened, a fetid smell emerged for a moment and people didn't look in till it dissipated.

Then one by one everyone had the opportunity to look in and Fleetwood said, "There was Lincoln in person." He told me that the eyebrows were gone. The beard was in place. The pillow underneath his head had decayed enough so that the head had turned at an angle as it fell back a little but it was okay. His clothing was the original suit that he was buried in, with the remains on it like a silk American flag that had dissipated -- red, white and blue. Someone had laid a flag on the breast of the president. The stock tie was in place.

He said that Lincoln looked white. When Lincoln was on his funeral journey his body had turned dark, and starting in New York City, they had begun to chalk the features. By the time the remains got to Springfield they were really a brown color. Fleetwood said the attempt to chalk the face of the president could be seen, but a light, white mold had replaced the dark and Lincoln had turned white again.

He said to me, and I'll never forget it, "Any school boy would know that it was Abraham Lincoln." There was no question it was the president that everyone had grown up with in pictures. So he took one last look -- everybody had their last look -- and then the plumbers resealed the coffin as they had done before, and they put the lid back on. Fleetwood said he helped them man the ropes to lower the coffin into the 10-foot-deep gravesite. He said that he was one of those who was the last to let go of the rope as they put in the president's remains.

Then metal bars were placed over the coffin and cement was poured from above so the coffin was encased in metal and cement, never to be disturbed again. In 1876 Robert Todd Lincoln, the president's son, had been horrified and Mrs. Lincoln had been alive at the time, when the there was an attempt to steal the body. It was Robert's memory of that which bothered him, thinking that after his own demise that his father's body could still be taken.

So it was Robert who designed the gravesite. We still don't know why Robert separated his mother and his father in the burial chamber. Before that time (even though after 1876 there was no body in the sarcophagus -- the sarcophagus remained visible and people honored an empty box) President and Mrs. Lincoln were together under the shaft of the tomb. [Mary Lincoln died in 1882.] Robert separated his parents in the final design of the grave. So that's why Lincoln is alone and Mary and the children are in the crypts behind his.

Fleetwood said he remembered the experience clearly. He could still recall seeing the face and as a 13-year-old boy he realized then that it was a lifetime experience. Then I shared with him that I had been about the same age when I found the photograph when he saw the president's remains. So Fleetwood and I have that in common.

When I was present at a conference in Springfield on Lincoln's Birthday a few years ago, I was talking about Fleetwood with someone. A man came up behind me and said Fleetwood was his uncle. He didn't know that anyone remembered Fleetwood Lindley.

It's interesting to think that as a boy I found the last photograph of the president in death, which triggered a phone call from James Wheeler of Des Moines whose father was Lincoln's White House gardener [Thomas G. Wheeler]. James Wheeler knew the president as a six-year-old, and Lincoln teased him about stealing some figs off a White House tree. His father took him to see Lincoln's body at the Rotunda in the U.S. Capitol. So in some strange way my life has been connected directly with the death of President Lincoln. Not only in 1865 but in 1876 because of the stealing of the remains; they were sealed up, moved out of the coffin, then in 1901 were placed where Fleetwood Lindley saw them.

Probably one of the greatest events for me in my Lincoln career was the dedication of the Bollinger Lincoln Collection because I met all the Lincoln scholars except Carl Sandburg and they were good to a boy. Out of that, the boy took it and made a career of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment